The Manifesto for Player-Centred Design

Why empathy is the core of building great games, adapted from my NZGDC 2018 keynote

Background

I was invited to give the closing keynote at the New Zealand Game Developer’s Conference, in Auckland in 2018.

Unfortunately the recording never surfaced online, and many things happened in the meantime that meant I never wrote up my talk. So, four years late, I’m offering my key takeaways on building a Player-Centred design culture in teams, here!

Making games we want to play isn’t good enough anymore.

Empathy has emerged as a central tenet in broader design culture, with accessibility and user-centred design pushing the boundaries of how and why we design the products people interact with on a daily basis.

Our audience is ever-broadening; everyone plays games now, but it’s still an insular and often close-minded group of people who make them. It’s no longer good enough to make games we ourselves will love- our players deserve so much more than that.

To combat this I created the Manifesto for Player-Centred Design. A call to action, a set of principles- a mindset for getting over your ego and making games everyone can love.

So, what’s the Manifesto?

First - Player-centred design helps make all games better

Second - You are not your player (probably)

Third - Make games everyone can love.

1. Player-Centred Design helps make all games better

As game makers, we are creating experiences for people to enjoy. However, we often approach our game development from a perspective of auteurship- names like Miyamoto, Moleyneux (wow you can tell the talk is old) lend confidence to the projects they create.

In other parts of the tech industry, user-centred design is a non-negotiable. That means putting your user’s needs at the core of the product, often above your personal opinions on what is best for them.

User-centred design methods scare some game creators, who see it as a path to making generic, creatively devoid projects. I disagree- because of friction.

Traditional UX is binary in the questions it asks, games UX is ephemeral.

That is the nature of fun. Creating friction is harder than building for pure usability.

To create the right level of friction, we have to deeply understand our players abilities, expectations and needs. If we don’t bring them into the heart of our design process, we can’t create the right level of friction to make the experience resonate with them!

Some games will fall further to the left or right of authorial intent versus audience perception. But ultimately, giving up some of our authorial intent can in fact make our games better four our players. Isn’t that the point?

2. You are not your player (probably)

The community of game developers does not often represent the demographics of the players we’re making it for. This is still treated with a certain level of derision in various parts of the industry- from generalising all casual mobile players as SAHMs with their husband’s credit cards and no impulse control, to expecting all players of your MOBA to be rude teenagers.

These days, everyone plays games. They may not look like what you expect.

When your team itself isn’t diverse, it is more difficult to create experiences that are meaningful to a wide audience. We tend to presume other people use technology in the same way that we do- but we all interact with games in different ways, and with different motivations.

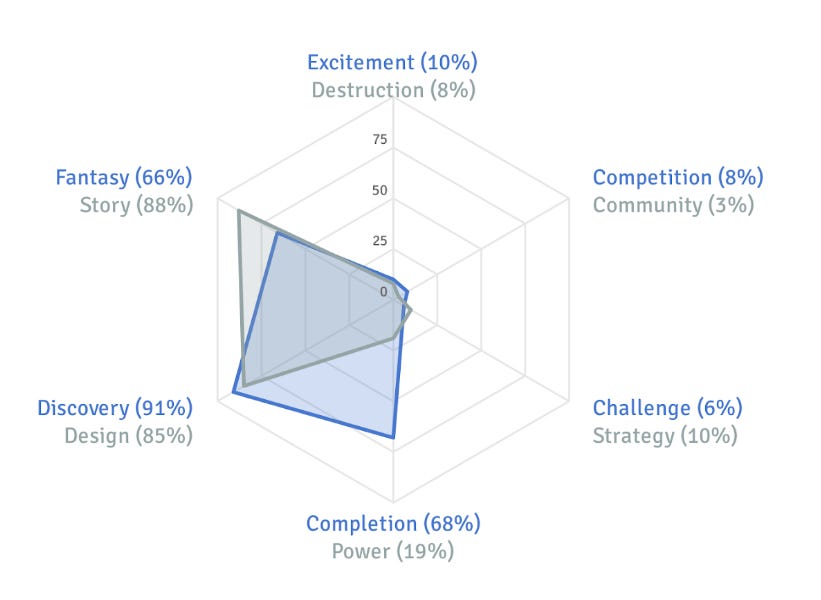

The more you can recognise your own biases and interests the better you can make representative, empathetic experiences. There is external research on this (from IGDA, Google and Quantic Foundary) but internal research about your audience must also be conducted. Combining this with a diverse team is the best way to design for players’ real needs and desires, and therefore make a more appealing game.

3. Make a game everyone can love

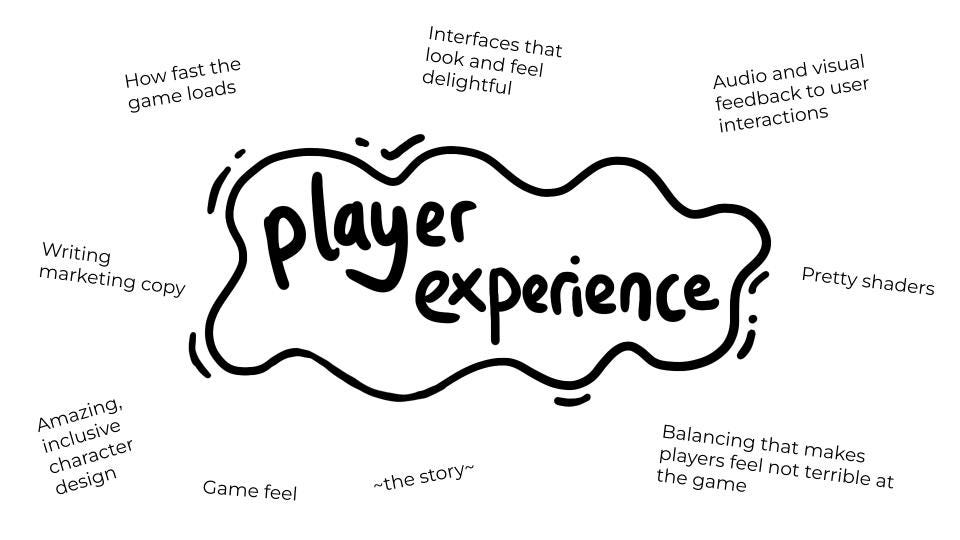

Many will argue that player-centred design is the responsibility of your UX designers. I’d argue that creating player-centred experiences is everyone’s responsibility, because so much can affect it!

UX design is a glue job, where we stick together design and code to make the end experience for the user as cohesive as possible. When the teams we work with are empathetic and interested in player-centred design, this makes our jobs all the easier- and results in better player experiences.

So, how can you develop a player-centred mindset, no matter what your game dev discipline is? By…

Participating in user research. Whether it’s facilitating or just viewing videos- it will massively increase your empathy for your players. In my experience, when developers see first-hand the problems their users are facing, they feel more empathy for them and are more likely to want to solve the issues those players are facing.

Immersing yourself in the communities of players like yours, and games like yours

Showing a broad group of people your work, early. We’re historically overprotective about letting in our audience on the magic. But it’s not user-centred design if you don’t put it in real peoples’ hands. There’s no way to test if your hypotheses are true if people don’t get their hands on it! Your game will always be tested – either on your terms or on the market’s.

Become your team’s advocate for accessibility. The Game Accessibility Guidelines tell this better than I ever could- my go-to resource.

With this new knowledge, it's our responsibility to take our newfound knowledge about our players, our biases around them, and the value of player-centred design to make our games better.

In Closing…

If you’re going to take anything from this talk newsletter, let it be this

Player-centred design helps make all games better. It’s a mindset, not a discipline. If you touch the game you’re affecting it.

You’re not your player! You may be one of them- but it’s easier to learn more about who they actually are

Make a game everyone can love. It doesn’t need to appeal to everyone, but if you make it as accessible as possible you broaden your audience immeasurably.

What do you think? Do you agree with the Manifesto?

It’s clear our culture of design has changed in the games industry in the intervening four years. I’m just happy most games companies recognise the value of UX designers, these days!

Peace out and see you next week, fam.

Cait

(PS - next week we’re going into the world of mentorship- don’t miss it!)

Link to the slides (they are very old, I’m warning you already)